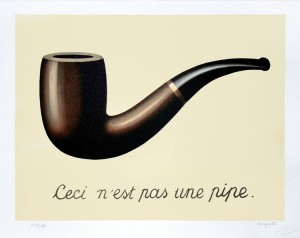

The nine individual blending components spanning a 3-year-period that will become my Gueuze style beer.

Update 4/2/2017 – This beer placed 2nd in the first round of the National Homebrew Competition and will be moving on to the final round at Homebrew Con in Minneapolis.

All the way back in 2013 I started what was both my first mixed-fermentation beer, as well as the first part of a three-year long project to produce a Belgian Gueuze style beer. When I started the project, three years was an almost impossibly long time for me to look into my brewing future. I had only recently begun brewing again after a nearly seven-month hiatus following a cross-country move from Seattle to NYC. Committing the space, time, and cooperage to an extended project like this was definitely a leap of faith. But the funny thing with time is that it makes a habit of flying by and here I am, three years later, writing about my Gueuze blending experience.

In many ways, Gueuze transcends the boundaries of what we typically consider beer to be. While the ingredients are basically the same as most beers we know, to those uninitiated to the world of sour, it is an entirely different beast. Acidic, fruity, funky, earthy, spicy, dry, spritzy—all of these commonplace Gueuze traits add to the synergistic complexity characteristic of these beers. It is a balance obtained through a rigorous blending process which ultimately produces a harmonious beer comprised of individual characters that on their own can be somewhat polarizing.

For me, Gueuze stands out not only for its delicious character, but also for the almost mythic process in which three annual vintages of Lambic beer are blended together to create the Gueuze blend. There is a romantic notion associated with the idea of blending different vintages of wild beers to create a happy harmony that is greater than the sum of its parts. It is pure liquid alchemy.

Blending Gueuze is not unlike the blending methods used by winemakers. As a vintner takes varying percentages of different grape varietals to produce a composite product, Gueuze production is approached in a similar manner. For my blend, I was able to choose between nine different 1-gallon batches—the result of splitting the original three batches three ways with secondary fermentation incorporating varying mixed cultures propagated from a host of commercial batches of beer.

2013

Base Culture: Wyeast 3278 Belgian Lambic Blend

Secondary Cultures:

– Cantillon Rose de Gambrinus

– Tilquin Gueuze

– Russian River Beatification

2014

Base Culture: Wyeast 3763 Roeselare Ale Blend

Secondary Cultures:

– Russian River Framboise for the Cure

– Jolly Pumpkin La Roja

– Blended House Culture of Various Origins

2015

Base Culture: Wyeast 3763 Roeselare Ale Blend

Secondary Cultures:

– Sante Adairius Cellarman

– de Garde The Duo

– Allagash Cuvee d’Industrial

Tasting and Blending

From left to right: the three-, two-, and one-year-olds.

Tasting nine individual batches of beer can be somewhat complicated. Simply keeping track of each beer is a chore, as is understanding the traits of each specific component. I found it necessary to simplify the process and hone in on specific traits and characters that I wanted to balance out in the final blend. I focused on trying to think about each beer in terms of broad categories: fruitiness, alcohol heat, sweetness, dryness, bitterness, astringency, acidity, and funkiness. Knowing that I would only be blending out five gallons from my 9-gallon stock allowed me to be picky and only choose the best of the class for my blend.

On my first pass, I found that specific samples stood out as delicious examples that could stand on their own while others exhibited specific off-flavors or traits that would be a problem in the final blend. The 3-year-old batches all exhibited a rather bitter/harsh/astringent character—something that I’ve since chalked up to the somewhat high levels of hopping these beers incorporated (using hops that were labeled as debittered, but which I suspect maintained a fair amount of their bittering capabilities). This trait made me confident that the final blend would likely only include these batches in a somewhat minimal fashion where the astringency would act to produce mouthfeel, balance, and complexity without being overbearing.

Four out of the nine batches stood out from their peers as being pretty exceptional on their own. All of the 2-year-old batches and one of the 1-year-old batches had a great balance with moderate to high levels of fruitiness, acid, and complex funk. These would act as the base for my blend.

Once all of the batches were methodically accessed, I began the process of producing a handful of test blends. Using a graduated pipette I created varying blends for trial. Having a second palate throughout the entire blending process was indispensable. Luckily, The Homebrew Wife was around to lend her taster and expertise to the process. We all have varying tastes and sensibilities when it comes to beer. Having two or more tasters at your disposal helps to ensure you’re not blending something that is flawed due to a blind spot in your own taste buds.

Ultimately, the final 5-gallon blend utilized seven different blending components:

10% – 2013 w/ Tilquin Gueuze

20% – 2014 w/ Russian River Framboise for the Cure

20% – 2014 w/ Jolly Pumpkin La Roja

20% – 2014 w/ Blended House Culture of Various Origins

10% – 2015 w/ Sante Adairius Cellarman

2.75 gallons of the leftover beer was racked over to a clean carboy with 3 lbs of apricot puree for additional aging.

Packaging

After such a commitment of time, it was with a lot of anxiety that I packaged this beer. My main concern was achieving a high level of carbonation in the beer. This presents a challenge in terms of choosing the proper bottles as well as ensuring that the yeast in the beer can ferment out the priming sugar in such a harsh, acidic environment.

To achieve a high level of carbonation, I primed the beer with dextrose to a calculated 3.1 volumes of CO2 with the anticipation that I may receive a slightly higher level due to a low amount of additional attenuation in the 1-year-old portion of beer. When priming a beer to this level of carbonation, it is extremely important to use heavy glass bottles specifically designed to accommodate high carbonation. Using standard beer bottles to carbonate to this level will cause dangerous bottle bombs!

To hedge my bets in terms of achieving carbonation at all, I packaged the beers with a fresh slurry of Safale US-05 yeast that had been fermenting in a wort starter that was pre-acidified to a pH of 4.0 using lactic acid. This strategy was employed based on research completed by Matthew Bochman from Indiana University in regard to terminal acid shock for bottling conditioning yeast in sour beers. The IU study concludes that using an acidic growth medium to pre-adapt yeast prior to bottling conditioning in acidic environments can lead to better consistency in successfully bottle conditioning sour beers.

Tasting Notes

Judged as 2015 BJCP Category 23E Gueuze

The Final Blend

Aroma (12/12):

The beer emits a beautiful nose that is both incredibly complex, but also very refined and well composed. The aroma starts with a prominent lactic component intermingled and energized by intriguing fruity aromatics reminiscent of both pie cherries and some bright tropical fruit. The bright fruit is kept in check by a substantial amount of barnyard funk with aromas of leather, earth, and hay. No alcohol, nail polish, or other common flaws found in sour beers. Fantastic.

Appearance (1/3):

The beer is a medium gold with just a whisper of haze. The head is bright white with medium to low persistence.

Flavor (20/20):

Amazing. The beer is highly acidic, yet remains soft and supple with a balanced and quenching disposition. Somehow underneath the cacophony of complex yeast and bacteria-derived compounds, a beautiful touch of slightly sweet pilsner malt character remains. There is a light touch of tannin, likely from the aged hops, that brings another balancing agent to the table. The flavors fall along the entire spectrum of sour beer, from fruit to funk with beguiling flavors that elude flavor description. One of the best beers I’ve tasted.

Mouthfeel (5/5):

The beer leaves an overall impression of dryness and effervescence. The beer is quite light bodied, but the acidity provides a soft roundness.

Overall Impression (10/10):

It is not hard to love a beer when you are acutely aware of the dedication and sustained effort required to produce said beer. But falling in love with a beer is a whole different matter. And I am definitely in love with this beer. I can unequivocally say that this is the best beer I’ve ever created and believe it would hold its own if consumed alongside some of the best sour beers in the world. The beer manages to be wonderfully complex, but also incredibly approachable and highly quenching. Having learned a great deal about long-term aging, mixed-culture fermentation, and blending in the process of creating this beer, it is profoundly rewarding to have also arrived at such a satisfactory end product.

Outstanding (48/50)

Looks like I’m not the only one that loves this beer.